In the late 13th century, after the death of Alexander III, eeccotland was left without a King. His heir Margaret, died soon afterwards, and the nobles of Scotland came together to rule Scotland (to be known collectively as the Guardians of Scotland). Three claimants to the throne emerged, John Balliol, the Comyn and Robert Bruce. The Scots sought the aid of King Edward I (“Longshanks”) of England to adjudicate the contest. Edward quickly exploited this situation to the utmost and, soon after placing the weaker Balliol on the throne (known by many as “toom tobard”, meaning empty coat,) invaded Scotland and named himself overlord. At this low point in Scottish History most noblemen and clans, due to the overwhelming power held by Edward, were forced to pay homage to Edward and to England. Few held out against the English overlord, but it was they who became the backbone of the Scottish fight for independence. In particular, four men of note refused to submit to the English domination: William Wallace (considered by many Scotland’s greatest hero,) John de Soulis, Simon Fraser, and William Oliphant.

Portrait of Wallace; by the 11 Earl of Buchan

Sir William Oliphant of Aberdalgie, known in many history books as “the gallant knight”, was a champion of Scottish patriotism (see how an Oliphant Knight may have looked in the 14th Century.) He was held in high esteem by the Guardians of Scotland, who placed him as governor of the most pivotal Scottish stronghold of Stirling Castle.

An artistic reconstruction of Stirling Castle as it may have looked in

the 14th Century by Andrew Spratt

Stirling Castle changed hands many times throughout the wars of Independence, as it was considered to be the most strategically important castle in all of Scotland. After the Guardians of Scotland reclaimed Stirling in the early 14th century, a garrison was placed at the castle under Sir William Oliphant *9.

In 1304, Edward resumed his reign of terror on Scotland, intent on capturing the last stronghold left in the hands of the Guardians of Scotland, and with it, Sir William. Oliphant, commanding 50 or so brave highlanders (including 3 other Oliphants,) with his cousin Sir William Oliphant of Dupplin as second in command. Sir William of Aberdalgie refused to accept Edward I’s conditions of surrender, a challenge to which Edward gladly took *10. Great crowds of English and Scots came to watch the siege and even the Queen was present, a hole being cut out the wall of a house nearby, so that she could be entertained in comfort. Sir William saw no end to the siege in sight, and as his garrison was cut off from supplies, asked that Edward allow him to send a messenger to his master (perhaps Wallace, but more likely the head of the Guardians at the time, John Balliol, King of Scots), to see if it was in his wishes that Oliphant and the garrison surrender to the English *11. Edward refused this simple request, for the reason that he wanted to test his war engines (trebuchets to catapult large stones or diseased carcasses into the castle), which bore such names as the Ram, the Vicar, and the War-wolf. These great siege engines (13 in all) were employed, and commanded, in one of his stints of allegiance to the English sovereign, by Robert Bruce *1. Oliphant defiantly held the castle (to which William Wallace himself visited many times during the siege, bringing clandestine aid to Oliphant *2) as were the original wishes of the Guardians, for more than three months, until August of 1304, when Oliphant was forced into surrender. He was paraded in front of King Edward with his men, naked, and chained by the neck *12, when he asked for the mercy of his men. Edward reputedly answered, “ask not for mercy, ask what is my will”, meaning that he, as a great king, had already made his mind to have Sir William killed. However, the Queen, having witnessed the siege, and the gallant defence put up by Scots, begged for the mercy of the commander, which request was granted. Sir William was imprisoned in the tower of London.

Robert the Bruce: arguably Scotlands greatest King. His

daughter Elizabeth, married Walter Olifard of Aberdalgie

(great grandson of David Olifard) ; making Robert the

ancestor of many, if not most, of the Oliphant Clan.

After four years, Sir William Oliphant of Aberdalgie was released by King Edward I’s son, Edward II, following Sir William having agreed to do the king’s work. He was placed as keeper of Perth, and was attacked there in 1312, ironically, by Robert Bruce, who had attacked him on behalf of the English at Stirling Castle. Bruce was held out of the town for 2 months by the garrison under Oliphant, until a midnight raid, led by Bruce himself, allowed Bruce to capture the town. Oliphant’s defence of Stirling seemed not to be forgotten by The Bruce (to this day a plaque to Sir William Oliphant of Aberdalgie is set into a wall Stirling Castle,) as he was the only man of importance that was not executed by Bruce’s forces, being sent instead to the Isles to be held *3. It is believed that he died during his exile to the Isles, as he “appears no more in record(s)” according the the Scots Peerage *13. It is therefore thought that the Chiefship passed on to Sir William Oliphant of Dupplin (possibly son, but more likely cousin to the above Sir William, and second in command at Stirling.) This Sir William is believed to have led members of the Clan at Bannockburn (although there has yet to be research done of Sir William’s part at Bannockburn, it is presumed significant as in 1317 he was given many charters of land by the Bruce, some of the lands being previously owned by the Comyn. Amongst these lands given by the Bruce include Newtyle, Kinpurnie, Auchtertyre (in Angus, where Hatton Castle now stands,) Muirhouse and Gask.) This Sir William Oliphant was the one who attached his seal to the Declaration of Arbroath *14 (see History).

Seal attatched by Sir William Oliphant

to the Declaration of Arbroath, 1320

Oliphant, after the wars of Independence, became a trusted friend of the Bruce (despite the Bruces two famous clashes with the previous Oliphant Chief). Sir William’s son, Walter (was probably named after Olifards living in Scotland some 200 years earlier. Since Thomas Kington-Oliphant’s otherwise scholastic book “Oliphants in Scotland” many have believed the Oliphant origin to have been Norse via Normandy and not Norse directly. This ignored and has not been borne out by examination of the facts (see the treatise entitled ‘Norman Herring’) Walter married Elizabeth, a daughter of Robert Bruce by his second marriage, and through this marriage recieved high standing and other lands including Kellie.

The Oliphant Clan homeland can be seen cirlced above

Walter’s descendant, a Sir Laurence Oliphant of Aberdalgie (son of Sir John Oliphant of Alberdalgie, who had been knighted by Robert II and who was killed at the Battle of Arbroath fighting alongside the Ogilvies *15, the Clan of his wife Margaret (see Battle of Arbroath) was created the 1st Lord Oliphant. The 1st Lord was one of Scotland’s ambassadors to England, and later to France (a prominent position, as Scotland and France (the two countries comprising the famed “Auld Alliance”) had often allied against the powerful English.) Laurence later became keeper of Edinburgh Castle *16, and was elected to act on behalf of the Scottish government (along with the Duke or Argyll, Lord Drummond, William Elphinstone, Lord Lyle, Archibald Whitelaw, and Duncan Dundas,) in order to keep the peace between Scotland and England *17. He had three sons, John, who became the 2nd Lord, William, from whom descended the Oliphants of Berriedale, and George who became Oliphant of Bachilton (in Angus). This William married Christian Sutherland, the daughter and heiress of Alexander Sutherland of Duffus (a marriage that was partly responsible for the myth that the Oliphants were a sept of Clan Sutherland, see Clan Relations). Through this marriage, William (who thereafter was styled Oliphant of Berriedale), received approximately a quarter of the entire county of Caithness, including the castles there of Oldwick and Berriedale in Caithness, and the land of Strabrock near Edinburgh.

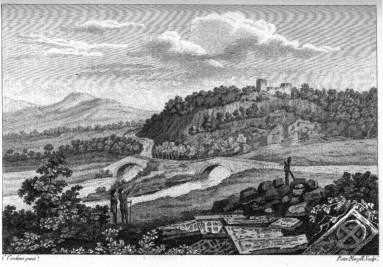

Sketch of Berriedale Castle in 1700s

During this period of the early 16th century, James IV, in loyalty to France, who were at war with England, drove the largest Scottish army ever assembled (estimated at 20,000), and met the Earl of Surrey at Flodden in 1513. The war was disastrous for the Scots, many of whom fell with their proud King, including the then Chief of Clan Oliphant, Colin, Master of Oliphant (son of John, 2nd Lord, and Elizabeth Campbell, daughter of Colin, chief of the Lochlow Campbells), and Laurence Oliphant, his brother, who was the Abbot of Inchaffray.

William Oliphant of Berriedale begat Andrew, who, having no male heir, ceded the land to his chief Laurence, 3rd Lord Oliphant (son of Colin, master of Oliphant, and Elizabeth Keith, daughter of the Earl Marishal), in return for Laurence finding suitable matches to his 3 daughters Margaret, Katherine, and Helen. This Laurence made his seat in Caithness, and the Oliphant Clan came into conflict with the clans of the North, including the Dunns, Sutherlands, and most notably the Sinclairs (the Chief of the Sutherlands, and the Lords Oliphant, later signed a mutual bond of manrent, as they were both troubled by the Sinclairs. This further perpetuated the myth that the Oliphants are a sept of the Sutherlands.) Of this rivalry comes a story that survives in Caithness to this day. While Laurence (who was said to be fond of the chase) was out hunting around the hill of Yarrows in Caithness, he was ambushed by a group of the Sinclair clan, including their chief, the Earl of Caithness. Oliphant was without attendants but had a fast horse, which took him back to Old Wick Castle (also known as Castle Oliphant.) Upon arrival, Lord Oliphant found the drawbridge up. His pursuers were close, and he hadn’t even time to sound his horn. At this moment, the bold Lord Oliphant made the decision to jump the moat which separated the castle from the rest of the promontory on which it stood (approximately 25 feet in all) and, in a single leap, his stallion carried his master over the chasm, landing him safely and unharmed to the other side.

The chasm said to have been jumped by Laurence Oliphant,

3rd Lord. Ruins of Old Wick Castle are seen in the backgroud

In the mid 1500’s, George, the Earl of Caithness, held an heritable Justicary of Caithness, Sutherland, and Strathnaver from Portinculter to the Pentland Firth, making him the final legal arbiter of all crimes, including rebellion. He greatly abused this power to his own benefit against his many enemies of the area, including the Oliphants. In 1569, his son John, Master of Caithness, besieged the Lord Oliphant at Old Wick. The clan present held out for 8 days, but were forced to capitulate due to “viveris specielle watter”, the lack of food and water. Later in Court the 3rd Lord appealed to the Privy Coucil “that it is not possible for (him) to get justice in a court presided over by the Earl of Caithness”, and that he wanted an impartial tribunal, but this request was denied.

After relations between James V of Scotland and Henry VIII of England soured, James raised an army of 15,000 men to advance into England, meeting there the Earl of Wharton. This war was unpopular among the Scottish Lord’s, however Laurence, 3rd Lord Oliphant, as the Clan was known to be constant supporters of the Stuart Kings, went to the Battle of Solway Moss, under, ironically, the “King’s favourite”, Oliver Sinclair of Pitcairns (a branch of the Caithness clan). The army was again routed, due to the infighting and overall unpopularity of the war. Laurence was captured and later ransomed.

Laurence, 4th Lord Oliphant (son of the 3rd Lord), was a supporter of Mary Queen of Scots. He was one of those who acquitted Bothwell for the murder of Darnley, and signed the bond for and attended the Royal Marriage. He fought at the Queen’s final defeat at Langside. Laurence, 4th Lord, lived out his days in Caithness, dying there in 1592.

The son of this Laurence, Laurence, Master of Oliphant, was involved in one of the events that brought down the chiefly line of the Oliphants from their position of power in Scotland, the Raid of Ruthven. James the VI of Scotland became king at 13 months of age, after his mother, Mary Queen of Scots, was forced to abdicate. As James was obviously unable to rule a country, he became a pawn in the struggle for power during the height of tension brought on by the reformation. He was raised a Catholic, but was however pressured by the Scottish nobles, many of whom were Protestant. He was closely associated with his cousin, Esme Stewart, successively the Earl (1580) and duke (1581) of Lennox. Although both Stewart, and James VI, declared themselves in favour of the reformation, it seemed to the militant Presbyterians (led by William Ruthven, Earl of Gowrie) that James was being pressured by the Duke (who was raised in Catholic France, and was a supporter of the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots). Their fear was so great of a counter-revolution, that they kidnapped the young King in 1582, while he was out hunting in Atholl. The next day, he signed a document proclaiming that he was free, and that the Duke of Lennox was to be banished from Scotland. James VI was held in the House of Ruthven for almost a year, while the Protestant coup effectively ruled Scotland to their own benefit. James escaped during a visit to St. Andrews. In 1584, the conspirators tried again but this attempt was foiled by the arrest of the Earl of Gowrie who was duly executed. The Masters of Oliphant and Morton (brother in law to the said Master of Oliphant) managed to escape, and were never seen again; their boat was lost at sea, said to have been captured by dutchmen, but later storied abouned that they were enslaved by Turks in the Mediterranean Sea. One Robert Oliphant went to Algiers to try to find them, and there is said to be a plaque in the church there of these two young men.

The Oliphants fell off the map politically after the death of the 4th Lord Oliphant, The son of the above mentioned Master of Oliphant, also named Laurence, was named the 5th Lord Oliphant. Due to the actions of his father, and his confused Catholic/Protestant upbringing (his father being Protestant, and his grandfather Catholic), the 5th Lord dissipated the Oliphant lands in full,including the ancient Oliphant lands of Aberdalgie and Dupplin to the Hays, who subsequently became Viscounts Dupplin and later still the Earls of Kinnoull, both titles still held today. Notably, he sold the extensive Oliphant lands in Caithness to the Earl of Caithness in 1604; Muirhouse was sold in 1605, and Kellie Castle (which by then had been in Oliphant hands for nearly 300 years) in 1613; Newtyle and Auchtertyre in 1617; and Gask was sold in portions in 1610 and 1614 to a cadet line. By 1625, the Gask branch were recognised as the Oliphants of Gask under the Great Seal. The King (Charles I) was present in court when Anna, the 5th Lord’s daughter (who was married to a younger son of another noble line) was fighting with her father’s cousin Patrick (son of John of Newtyle, who was the son of Laurence, 4th Lord Oliphant) for the title. The King required the title be surrendered to the crown and then created Anna’s husband the first Lord Mordington together with the precedence of the Lordship of Oliphant. He then made Patrick (and the heirs- male of his body) the Lords Oliphant (Patrick being the 6th Lord). The title passed thereafter successively to Patrick’s son Charles, 7th Lord, to Charles’ son Patrick, 8th Lord, to Charles’ brother William, 9th Lord, and to a nephew of Charles’, Francis, 10th Lord. In 1748, this line died out, thus ending the Lordship of Oliphant and with it, pro tem, the chiefship.