Setting the Stage

After the death of Elizabeth I of England, James VI of Scotland succeeded to the throne of England, to become James I, first of the Stuart line of English sovereigns. He reigned over both kingdoms until his death in 1625, at which point his son Charles I, ascended to the throne. Charles was in great collision with his subjects (both in England and) in Scotland, due to his suppression of the Covenantors. During this time, Charles appointed the Marquis of Huntly (the Chief of Clan Gordon,) to defend his position in Scotland. The Oliphant Clan (constant supporters of the Stuarts) fought with Huntly and Charles. Patrick, 6th Lord Oliphant, being a close confidant, was present at the meeting between Huntly and Montrose in 1639 *25 (who at that time was the head of the militant Covenantors,) as was common at the time in case the meeting turned violent. However, Charles I’s opposition eventually got the better of him in the civil war and the Commonwealth (the established parliament in England,) as it is called, tried Charles I in court, where he was convicted of “making war on his parliament” and was executed. There followed years of government under the Commonwealth and under the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell (as well as a short stint by his son, Richard.) Charles, eldest son of Charles I, was believed by most Scots to be the rightful ruler of Scotland and, after the execution of his father, left his exile in Hague and was crowned at Scone in 1651. He was twice defeated by Cromwell and eventually retired into exile in France. After the death of Richard Cromwell (who had none of the genius his father used to rule England,) Charles II of Scotland was immediately crowned King of England by the English who had endured over 30 years of Civil war in the hopes of expelling the tyranny of a Monarch. This ironic twist of events came as a great surprise to many, including the then Chief of Clan Urquhart, Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty, who it is said died of a fit of laughter on hearing of Charles II restoration *6. At the latter’s death in 1685, his brother James ascended to the throne and became James VII of Scotland and II of England.

Portrait of James VII of Scotland, II of England

The Roots of the Jacobite Movement

This sovereign was almost immediately disliked by the English (barring the Catholics,) and the Covenantors (Presbyterians) in Scotland, due to his staunch adherence to the Roman Catholic faith. He succeeded in alienating the majority of the aristocracy in England and the powerful covenanters in Scotland, his only support on the Isle being from the Episcopalian and Catholic Clans. William of Orange, the Protestant Dutch prince, was invited to the throne in 1688, to which he ascended with Mary (sister of James.)

Here begins the history of the Jacobites (from the Latin translation of James, Jacobus.) The Covenantors in Scotland resolved to place King William and Mary on the throne of Scotland. This was disputed by many of the powerful highland Clans (mostly Catholic and Episcopalian,) who believed James to be the rightful king of Scotland. These supporters of James became known as the Jacobites. Clan Oliphant, as a mainly Episcopalian Clan and as devoted followers of the Stuart Kings, became staunch supporters of the Jacobite movement.

John Graham, Viscount Dundee

William, later to be the 9th Lord of Oliphant, was a valiant soldier, fighting for Scots regiments in Spain, Flanders, Belgium, and Ireland *21. He then returned to Scotland in 1689, to represent his Clan in the Jacobite movement. He was created lieutenant-colonel at the head of a company of foot in his cousin Viscount Frendraught’s regiment. He led the Clan under Viscount Dundee (John Graham of Claverhouse) at Killiecrankie in 1689 *22, where the Jacobites won their greatest victory over the Covenanters. Unfortunately, their great general Dundee fell near the conclusion of his victory with a shot under his arm. This dampened the Jacobite spirits greatly, the rising becoming somewhat dormant. After many Jacobites returned home, William and the Clan stayed loyal to the cause. William, along with his cousin Frendraught and a few other Jacobites, took control of Federate Castle in Buchan, which they held against Mackay for more than 3 weeks *34. This became the last stronghold held for King James on the Scottish mainland, and after its capitulation in October of 1690, William Oliphant and the other men were made prisoners. The Privy council ordered William’s release the next year, as the sympathisers to the Jacobite cause waited for an opportunity to reinstate James to the throne.

After James II death in 1701, his son James Francis Stuart (nicknamed the “Old Pretender” by many, who believed that he was not the son of James II,) was taken by the Jacobites as being the true King of Scotland. In 1707, the act of the Union was passed, uniting Scotland and England. This act was unpopular in Scotland, many of the Jacobites, including Patrick, 8th Lord Oliphant, voted against the union *26. Because of this popular discontent, James returned from his exile in France in 1708 (sponsored by Louis XIV, who aided James less out of adherence to the “Auld Alliance”, and more out of the hopes of taking some of the English might off of his forces in Flanders.) However, the expedition became a fiasco, with James being unable to land at Fife because of the superior English fleet controlling the area. Again the Jacobite hopes were crushed.

The Rising of 1715

After Queen Anne’s death in 1714, the English Lords decided to place Sophia, grandaughter of James VI and I, on the English throne, instead of James, cousin to Queen Anne. At this point, the Act of Union was as unpopular as ever in Scotland and the Jacobites decided to take advantage of this by attempting to regain the Scottish Throne for James. John Erskine, Earl of Mar, had been a strong supporter of the Covenanters, had supported the Act of Union and the ascension of Queen Sophia to the throne. However, as he was snubbed by King George I (who was convinced of Mar’s Jacobite sympathies by others in the Union) of his position of Secretary of State for Scotland, he switched allegiance to the Jacobite cause (his reputation for changing sides when it suited his career, earned him the nickname “Bobbing John”.) The then Laird of Gask, James Oliphant, sent his two sons *23 (Laurence the Elder (later 6th Laird of Gask,) and James) to support his Chief, William, 9th Lord Oliphant and the Jacobites. Other Clan members of note include Alexander Oliphant, a lieutenant; Laurence, brother to the 9th Lord, a lieutenant; Francis, brother to the 9th Lord, a lieutenant; and David, a soldier; all in the Perth Company *24.

The Highland passion for the Jacobite cause was made clear with many rival clans joining the rising, including old foes the MacDonalds of Keppoch and the MacIntoshes (who fought the last Clan battle in Scotland at Mulroy in 1688); as well as the Campbells of Glenlyon and the MacDonalds of Glencoe (the Glencoe Massacre participants) joined, as their abhorrence of the Union and the support of their true king, proved stronger than their hatred of each other. The advantage seemed to be upon the Jacobites. Although Mar was an administrator and not a soldier, he would not give up his command of the army to a more proficient general (many suggested the leader of a party of insurgents that meant to gain support of the sympathetic lowlanders and English, William MacIntosh of Borlum.) This proved costly at Sherrifmuir, where he met the Duke of Argyll with the latter’s group of government forces (which numbered only half of the Jacobite army,) but Mar was unable to capitalise, as the battle ended in a draw, with the Clans returning home afterwards. Both Oliphants of Gask were present at the battle of Sherrifmuir in Lord Rollo’s regiment *27. After the battle, Laurence (son of James Oliphant of Gask) was one of the garrison’s adjutants during the short time James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) remained at Scone *28. After the suppression of the rising by the government forces (specifically under the Duke of Argyll,) Laurence stayed in the North of Scotland until he was given a safe passage home by the government forces. Laurence succeeded his father, becoming the 6th Laird of Gask in 1732.

The ‘Forty-Five’

Believed by the Jacobites to be the rightful King, Prince Charles Edward Stuart left Italy (where he had been raised) for Scotland, eventually landing on the Isle of Eriska in July of 1745. The Jacobites flocked to the standard of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Oliphants being no exception. Charlie made a tour around the highlands to gain the support of the Clans. At Blair Atholl, he was joined by Laurence, 6th Laird of Gask, and Lord Nairn (brother-in-law to Laurence.) Laurence attempted to gain the support of his tenants at Gask, many of whom would not take arms for Prince Charlie. Oliphant was so upset at this lack of faith, that he disallowed them the use of his property (this inhibition was later removed, on the advice of Prince Charles himself.) *29

Portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart

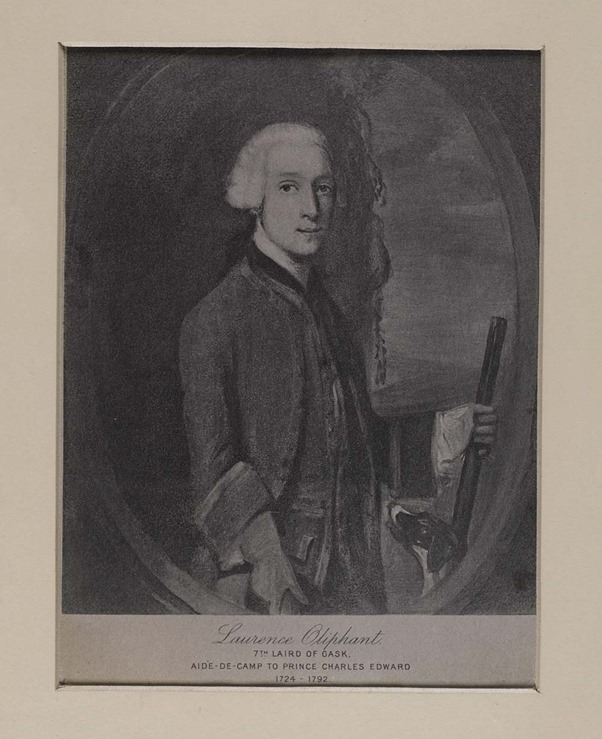

The Prince continued on to Perth, where he was met by his Highland Chiefs and Chieftains, including the Duke of Perth (Chief of Clan Drummond,) Lord Ogilvie, Lord George Murray, Lord Strathallan (brother to the Duke of Perth,) Robertson of Strowan, and Laurence Oliphant of Gask. He later breakfasted at the House of Gask on his way to Edinburgh, leaving a lock of his hair and pieces of his clothing to the family to commemorate the experience (these artifacts are today held at Ardblair Castle, the seat of Laurence Kington Blair Oliphant of Gask and of Ardblair, see Links.) Laurence, Laird of Gask and Laurence the Younger, (later the 7th Laird of Gask,) accompanied Prince Charlie on his excursion into England, the latter being an Aide-de-camp to Bonnie Prince Charlie *30. The two former, Laurence the Elder and Laurence the Younger, corresponded as Mr. White, and Mr. Brown. Laurence the Younger, while A.D.C to the Prince during 1745, also corresponded with his mother (see a Letter from Laurence to his Mother.) Later that year, Laurence the Elder was sent back North to set up a garrison at Perth.

The birthday of King George II was celebrated all over Great Britain, including parts of Scotland. A huge public display was made at Perth, where some Covenantors took control of the church at midday and rang the bells in celebration of King George. Laurence the Elder, the deputy governor of the town *31 (under Lord Strathallan,) took with him a small party of 3 or 4 in order to order those who rang the bells to desist. This order was ignored and, as Oliphant and his men were greatly outnumbered, they retired to the Council House in order to secure nearly 1500 arms held there. At night, 7 Jacobite gentlemen, along with their attendants, entered town, and immediately joined Gask at the Council House. At approximately 9 o’clock, Oliphant and the group went outside to disperse the ever increasing crowd, and fired upon them. The mob rushed upon Oliphant’s party, disarming and wounding some of them and forcing them to return to the Council House for cover. The mob demanded that Oliphant surrender and give up the arms in the council house, to which Oliphant bluntly refused. The garrison was fired upon until the crowd dispersed at about 5 o’clock in the morning. Oliphant was aided the next day by 60 of Lord Nairn’s men and later by 130 more of the Highland army, in the hopes of preserving order *32. Later, at the battle of Prestonpans, where Prince Charles’ forces routed the English, Laurence the Younger was again an Aide-de-camp to the Bonnie Prince. Also there fighting for the Prince, was the goldsmith, Ebenezer Oliphant *7. Afterwards, Laurence the Younger was sent to block the retreat of the English dragoons to Edinburgh. It is said that he slew 10 dragoons just on the way *33.

Laurence Oliphant, Younger of Gask (later 7th Laird of Gask)

The Laird of Gask was established with Lord Strathallan at Perth, to undertake the civil and military government of the North, Laurence’s responsibility being mainly that of treasurer.

Both Laurence the Elder and the Younger were at the Battle of Falkirk, where the Highland army under Lord George Murray defeated General Hawley and his English dragoons. Before the final battle of Falkirk (the battle was filled with maneuverings and small skirmishes,) Laurence the Younger, along with the son of Lord Strathallan, bravely entered the Camp of General Hawley, disguised as peasants, in order to procure intelligence, because of the belief that a ambush was being planned.

The Battle of Culloden

After the invasion of England had been cut short for want of provisions, among other reasons, the highland army retreated back to Scotland. Following the Battle of Falkirk, in which the Scots were marginally victorious, Prince Charles and his Highland Chiefs decided to retire to the highlands for the winter, and to regroup in the spring. However, by the time the army made camp in Inverness, news reached them that the Duke of Cumberland’s Army was only 15 miles behind them at Nairn. The next day the armies took the field at Culloden. The Highland army was depleted (due to deserters,) now numbering just over 4000; starving, most having not eaten in days; and exhausted from their march to England and back. Among the Highland Army was Laurence, 6th Laird of Gask and his son, Laurence the Younger, in the Duke of Perth’s Horse regiment. They were the only Oliphants of note present at the battle (joined by their attendants,) as the 11th Lord had lost all of his land and was in very ill health (dying in the same year,) so unable to raise any other of the Clan to aid Prince Charlie. Cumberland’s men were fed, well supplied veterans, just back from service in Europe. Along with these English troops were nearly 4,000 Scots, most lowlanders with the exception of the Campbells and some regiments from other Whig Clans. The battle was a complete rout (click here for a complete account of the battle.)

The Duke of Perth’s regiment held fast as many Highlanders involved in the initial rush began to retreat past them. After the signal to retreat was given, both Laurence the Elder, and the Younger, were able to escape, as they were both on horses. Following the battle, the house of Gask was routed and pillaged by English troops under Ensign Fawlie *4. Laurence the Elder was quoted as saying “God sent our rightful Prince among us, and I followed him” *5.

The Aftermath

After the battle, both Laurence the Elder and Laurence the Younger escaped east together, ending up in Aberdeenshire, where they were concealed by Jacobite sympathisers around the area of the Dee, narrowly evading capture on more than one occasion. Remaining in hiding there for about 6th months, a passage was arranged for them, and other prominent Jacobites, to Sweden, where they landed on 10 October 1746. They later fled to France, and set up a more permanent residence. They were allowed to return home in 1763 to Gask, although they were still considered outlaws, as their attainder was not reversed (the lands of Gask were seized by the government after Culloden, and were purchased back in 1753 by Laurence’s kinsman Ebenezer Oliphant, a wealthy Edinburgh Goldsmith of the Gask branch, and by the then Oliphant of Condie *8.)

Carolina Oliphant 1766-1845

Here at Gask was born Carolina Oliphant, a Scottish poet second only to Robbie Burns. She is known especially for her great Jacobite laments, written to cheer the wounded spirits of her father and grandfather, who never really recovered from the battle. Her most famous song, probably being “Will Ye No Come Back Again?”, a lament to Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Will Ye No Come Back Again?

Bonnie Charlie’s now awa’

Safely owre the friendly main;

Mony a heart will break in twa,

Should he no’ come back again.

Chorus:

Will ye no come back again?

Will ye no come back again?

Better lo’ed ye canna be,

Will ye no come back again?

Ye trusted in your Hieland men,

They trusted you, dear Charlie;

They kent you hiding in the glen.

Your cleadin’ was but barely.

Chorus:

We watched you in the gloamin’ hour,

We watched thee in the mornin’ grey;

Tho’ thirty thousand pounds they’d gie,

Oh, there was nane that wad betray.

Chorus:

Mony a traitor ‘mange the isles

Brak the band o’ nature’s laws;

Mony a traitor wi’ his wiles,

Sought to wear his life awa’.

Chorus:

Many a gallant sodger gaught,

Mony a gallant chief did fa,

Death itself were dearly bought,

A’ for Scotland’s king and law.

Chorus:

Whene’er I hear the blackbird sing,

Unto the evening sinking down,

Or merl that makes the wood to ring,

To me they hae nae other sound.

Chorus:

Sweet the lav’rock’s note and lang,

Lilting wildly up the glen;

and aye the o’erworld o’ he sang,

‘Will he no’ come back again?”

Chorus: